Last Updated on January 23, 2026 by Grayson Elwood

My name is Claire. I’m twenty-eight, American, and I grew up in the kind of childhood you learn to describe in clean, careful sentences because anything messier makes people shift in their seats.

I was raised in the system.

Before I turned eight, I had already learned how to live out of a bag. Not a cute overnight bag—something thin and temporary, always a little too small. I learned which adults smiled with their mouths but not their eyes. I learned how to memorize new hallways quickly. How to keep my shoes by the door. How to say “thank you” like it was a spell that might keep me from being labeled difficult.

People like to call kids “resilient.” I used to hear it like praise, like I’d earned something.

But resilience, up close, often looks like this: you stop asking questions. You stop expecting answers. You stop letting your heart settle anywhere long enough to be bruised.

By the time they dropped me off at the last place—the orphanage I’d later think of as my real beginning—I had one rule that lived in my bones:

Don’t get attached.

I repeated it the way other kids repeated bedtime prayers. Don’t get attached. Don’t get attached. Don’t—

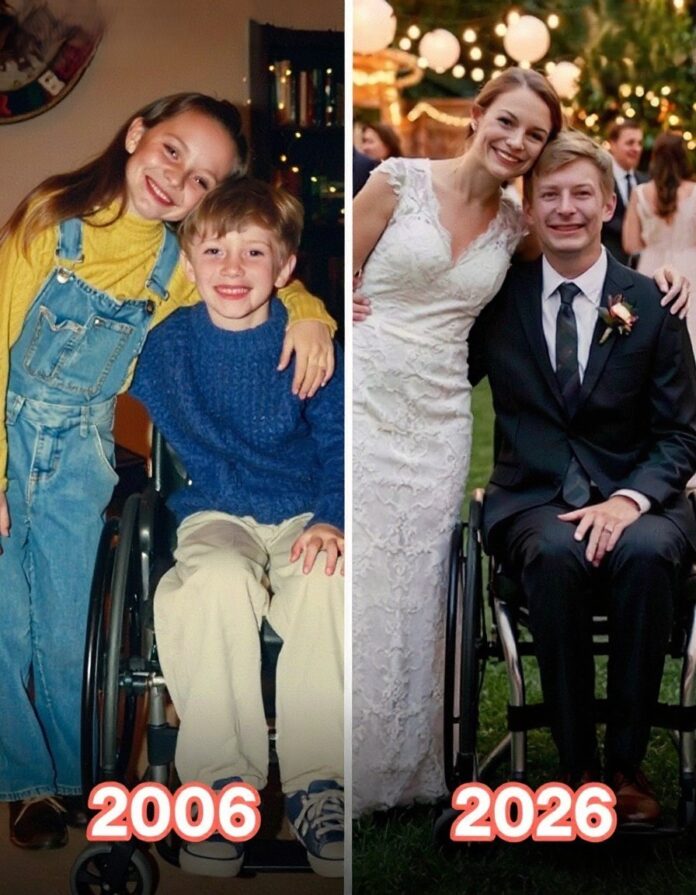

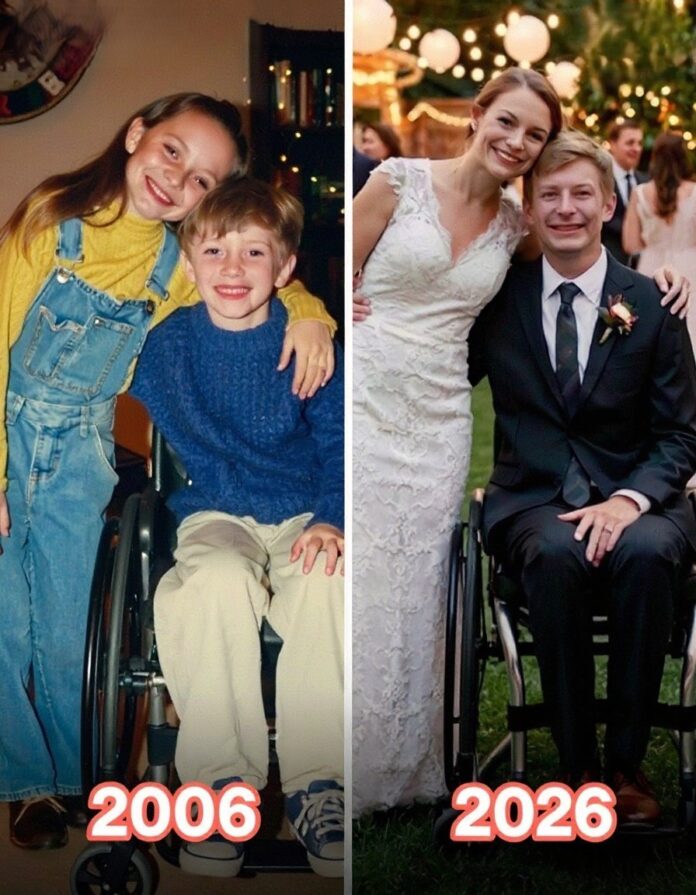

Then I met Noah.

It wasn’t dramatic. It wasn’t the kind of moment you’d notice from across the room and later frame in gold.

It was fluorescent lighting and scuffed linoleum and a smell like industrial cleaner that never quite left your clothes. It was a room full of kids who had all learned their own versions of my rule. A room where laughter came in bursts and then cut off, like everyone remembered at the same time that joy could be confiscated without warning.

Noah was nine.

He was thin in that way some kids are when they’ve grown around absence instead of abundance. His hair was dark and stuck up in the back, like it refused to follow instructions. His face was too serious for someone who still had baby softness in his cheeks.

And he was in a wheelchair.

Not the sleek, modern kind you see in glossy brochures. This one was practical, a little worn, the metal dulled in places from use. The wheels had that faint squeak that became familiar later, like a small signature sound that meant he was near.

Everyone around him acted… odd.

Not cruel, exactly. Just uncertain. Like they didn’t know whether to speak louder or softer, whether to help or pretend he didn’t need it. The other kids would call out a quick “hey” from across the room and then sprint off to play tag or soccer or anything that required legs that worked without thinking.

The staff spoke about him like he wasn’t fully in the room.

“Make sure you help Noah,” they’d say, right beside him, as casually as they might assign someone to wipe tables after dinner.

Not because they meant to be unkind. But because in places like that, you can become a checklist before you become a person.

Noah sat by the window a lot.

He wasn’t staring out like he was waiting for someone to arrive. He looked like he was watching the world the way you watch a movie you’ve already seen—quiet, alert, like you’re collecting details other people miss.

One afternoon during “free time,” I had a book in my hand and a stubborn knot in my chest. The room felt too loud, too full of bodies and restless energy. I scanned for somewhere to land that wouldn’t require conversation.

And there he was, by the window, angled just so, like he’d claimed that patch of light for himself.

I walked over and dropped onto the floor near his chair. The linoleum was cold through my jeans. My book slapped lightly against my thigh.

I didn’t look up right away. I opened my book like I belonged there.

Then I said, without thinking too hard about it, “If you’re going to guard the window, you have to share the view.”

For a second there was only the distant sound of shouting from the other end of the room, and the hum of the building, and the faint squeak of his wheel as he shifted.

Then he looked down at me.

His eyebrows lifted, just slightly.

“You’re new,” he said.

His voice had that careful quality—like he weighed words before letting them go.

“More like returned,” I said, because that was what it felt like. Like I’d been dropped into a cycle and tossed back when I didn’t fit where they wanted me.

I finally glanced up.

He studied me for a beat longer than most kids did. Not suspicious exactly—just thorough.

“Claire,” I added.

He nodded once. One precise motion.

“Noah.”

That was it. No dramatic handshake. No instant best-friend montage.

But something clicked into place anyway, like a door shutting softly against a draft.

From that moment on, we were in each other’s lives.

Growing up together in that place meant we saw every version of each other.

We saw the angry versions—the ones that came out after yet another kid got chosen by a “nice couple” with a minivan and matching jackets, while the rest of us lined up to smile like we weren’t calculating what it meant to be left behind again.

We saw the quiet versions—the ones that sank into themselves after phone calls that never came or birthdays that passed with no more celebration than a sheet cake cut into uneven squares.

We saw the versions of ourselves that learned not to hope too loudly when visitors toured the facility, because hope could make you sloppy. Hope could make you try.

And trying was dangerous when the outcome was so rarely in your favor.

Noah didn’t talk much about what he wanted.

Neither did I.

Wanting was a kind of hunger. Hunger made you restless.

But we had rituals.

Every time a kid left with a suitcase—or, more often, with a trash bag knotted at the top—we’d stand side by side and do our stupid little exchange like it was a comedy routine.

“If you get adopted,” Noah would say, his tone deliberately casual, “I get your headphones.”

“If you get adopted,” I’d fire back, “I get your hoodie.”

Sometimes we’d smirk like it was nothing.

Sometimes my throat would sting afterward and I’d pretend I was getting over a cold.

Because under the joke lived the truth: we both knew no one was lining up for the quiet girl with “failed placement” stamped all over her file. No one was flocking to the boy in the chair, either—not because he wasn’t worth it, but because people liked their love uncomplicated.

So we clung to each other instead.

Not in a dramatic, desperate way. In the ordinary way that two kids, left too long in uncertainty, find something steady and build a small shelter out of it.

As we got older, Noah’s seriousness softened into something warmer. He was still observant, still sharp, but he started letting humor in—dry, sometimes unexpected, the kind that made you laugh after a half-second delay because you had to catch up.

He noticed things.

Last Updated on January 23, 2026 by Grayson Elwood

If I was quieter than usual at dinner, he’d wheel closer and nudge my shoe with his, just enough to let me know he saw me.

lone.cmd.push(function () { ezstandalone.showAds(127); });

If a staff member snapped at him for taking too long in the hallway, I’d suddenly appear with some excuse—“Ms. Greene asked me to help”—just to create a buffer.

We didn’t make promises. Promises were risky.

But we were there. Over and over, we were there.

We aged out almost at the same time.

The day it happened, the office smelled like old printer ink and stale coffee. They called us in like we were being summoned to the principal’s office. A woman slid papers across the desk with the bored efficiency of someone who’d done it a hundred times.

“Sign here,” she said. “You’re adults now.”

Adults.

The word landed like a stone. Too heavy for how casually she said it.

I remember the scratch of the pen in my hand, the way my signature looked unfamiliar, like it belonged to someone older and more confident than I felt.

When we walked out, we had our belongings in plastic bags. Not even matching bags. Mine was cloudy and wrinkled. Noah’s had a tear near the bottom that made him keep adjusting it so nothing slipped through.

There was no party. No cake. No “we’re proud of you.”

Just a folder, a bus pass, and that quiet, terrifying weight of “good luck out there.”

Outside, the air hit my face like a reset—cooler, sharper. The sky looked too wide. The sidewalk felt like a boundary line.

Noah rolled beside me and spun one wheel lazily, like he was trying to act relaxed for my sake.

“Well,” he said, “at least nobody can tell us where to go anymore.”

I let out a breath that was half laugh, half something else. “Unless it’s some kind of official trouble.”

He snorted, and the sound was so normal it steadied me. “Then we better not get caught doing anything stupid.”

We didn’t have a master plan. We had each other and a stubborn willingness to work.

We enrolled in community college. We filled out forms with hands that didn’t quite stop shaking until we were halfway done. We learned which offices to call, which websites to refresh, which lines to stand in.

We found a tiny apartment above a laundromat.

It always smelled like hot soap and damp cotton and burned lint. The air was warm in a way that clung to your skin. The machines downstairs thumped and churned all day, like the building had its own heartbeat.

The stairs were awful. Noah eyed them once and then looked at me with an expression that said, Well, this is inconvenient.

But the rent was low. The landlord didn’t ask questions. The door had a lock that worked.

So we took it.

We split a used laptop that overheated if you asked it to do too much at once. We took any job that would pay us without making us wait weeks.

Noah did remote IT support and tutoring—his voice calm, patient, the kind of voice that made even angry customers settle down. I worked at a coffee shop during the day and stocked shelves at night, my body moving on autopilot while my mind tried to keep up with assignments.

We furnished the apartment with what we could find: a table that wobbled unless you shoved a folded napkin under one leg, a couch from a thrift store that tried to stab you with springs, three plates that didn’t match, one good pan that we guarded like treasure.

Still, it was the first place that felt like ours.

The first place where nobody could barge in and tell us to line up.

The first place where the quiet at night belonged to us, too.

Somewhere in the grind, our friendship shifted.

Not with fireworks. Not with a cinematic moment that made everything clear.

It happened in small ways, like most real things do.

I realized I always felt calmer when I heard his wheels in the hallway—the gentle squeak, the soft bump as he crossed the threshold. The sound meant: You’re not alone.

He started texting me, “Message me when you get there,” every time I walked somewhere after dark. Not controlling. Not dramatic. Just… careful. Like he’d decided my safety mattered to him in a way that was permanent.

We’d put on a movie “just for background,” and then we’d end up actually watching it, shoulders touching, laughing at the same parts. Sometimes we’d fall asleep before it ended—my head on his shoulder, his hand resting on my knee like it belonged there.

The first time I noticed how natural that felt, my chest tightened in a way that scared me.

Because attachment had always been dangerous.

And yet.

One night, we were half-dead from studying. The room was dim except for the glow of the TV menu screen. A faint breeze pushed through the cracked window, carrying the clean, sharp scent of detergent from downstairs.

I stared at the ceiling for a long moment, my thoughts circling something I couldn’t quite name.

Then I said, quietly, “We’re kind of already together, aren’t we?”

Noah didn’t even look away from the screen at first. He just let out a small breath—almost a laugh, almost relief.

“Oh, good,” he said. “Thought that was just me.”

That was our big moment.

No grand confession.

Just the truth, finally spoken out loud.

We started saying boyfriend and girlfriend because that’s what people did, because labels helped the outside world understand.

But everything that mattered between us had already been there for years.

We finished our degrees one brutal semester at a time.

When our diplomas arrived in the mail, we didn’t open them delicately. We tore the envelopes like we were afraid the paper might vanish if we didn’t grab it fast enough.

We propped them on the kitchen counter and stared like they were proof of something impossible.

Noah leaned back in his chair and laughed softly, shaking his head.

“Look at us,” he said. “Two orphans with paperwork.”

The words made me laugh and ache at the same time.

A year later, Noah proposed.

Not at a restaurant. Not in front of a crowd. Nothing that would make my heart pound from too many eyes.

It was a random evening, the kind where the light outside the window had turned honey-gold, and the apartment smelled like garlic and boiling pasta.

I was stirring sauce, hair shoved into a messy bun, wearing sweatpants and an old t-shirt with a faded logo.

Noah rolled into the kitchen like he had something to say, but he didn’t make a big production of it. He just reached into his pocket and set a tiny ring box beside the sauce, like it belonged among the everyday things.

Then he looked at me—steady, serious, soft around the edges.

“So,” he said, “do you want to keep doing this with me? Legally, I mean.”

For a second, my brain did that strange thing where it tried to reject the moment—like good things were suspicious.

Then my eyes stung.

I laughed, then cried, then laughed again because my body couldn’t decide how to hold that much warmth at once.

Last Updated on January 23, 2026 by Grayson Elwood

“Yes,” I blurted, too fast. “Yes. Before you change your mind.”

ne.showAds(127); });

His smile was small but bright, like sunrise through clouds. “Not planning on it.”

Our wedding was small and cheap and perfect.

Friends from college who had seen us grind our way through. Two staff members from the home who actually cared—the rare kind who had treated us like people, not projects. Fold-out chairs. A Bluetooth speaker that crackled once in a while. Too many cupcakes.

I wore a simple dress and sneakers because I wanted to feel like myself, not like I was playing a role. Noah wore a navy suit, and when he rolled into view, my breath caught.

He looked like someone you’d see in a movie poster—handsome, composed, the kind of man who belonged in the world.

But when his eyes met mine, I saw the boy by the window, the one who’d made room for me without hesitation.

We said our vows. We signed the papers. We kissed in a way that wasn’t flashy, just sure.

And then we went back to our little apartment as husband and wife.

That night, we fell asleep tangled up, exhausted and happy, the kind of happy that feels like a deep exhale after holding your breath for years.

The knock came late the next morning.

Firm, not frantic.

The kind of knock from someone who knew exactly why they were there.

Noah was still asleep, hair sticking up, one arm thrown over his eyes. His wedding ring caught the light when he shifted, a bright new circle against skin.

I slid out of bed carefully, pulling on a hoodie and stepping over the spot where the floor creaked.

My bare feet padded to the door.

When I opened it, a man stood in the hallway.

Dark coat. Neat hair. Calm eyes. Maybe late forties, early fifties. He looked like he belonged behind a desk, not in our chipped doorway with its peeling paint.

“Good morning,” he said, polite in a way that didn’t relax me at all. “Are you Claire?”

I nodded slowly.

Every alarm bell I’d ever developed in foster care started ringing at once. A man shows up. A man asks questions. A man carries authority in his posture.

“My name is Thomas,” he said. “I know we don’t know each other, but I’ve been trying to find your husband for a long time.”

My chest tightened.

“Why?” I asked, my voice sharper than I meant it to be.

Thomas glanced past me, not nosy exactly—more like he was taking in the reality of our life: the cramped space, the thrift-store furniture, the quiet effort holding it all together.

Then his gaze returned to mine.

“There’s something you don’t know about your husband,” he said. “You need to read the letter in this envelope.”

He held out a thick envelope.

Behind me, I heard the soft sound of wheels, and my heart steadied just a fraction.

“Claire?” Noah’s voice was rough with sleep.

He rolled up beside me, hair a mess, t-shirt wrinkled, ring still shiny and new. He blinked at Thomas, confusion knitting his brow.

Thomas’s expression shifted—softened—when he saw him.

“Hello, Noah,” Thomas said. “You probably don’t remember me. But I’m here because of a man named Harold Peters.”

Noah frowned. “I don’t know any Harold.”

“That makes sense,” Thomas replied. “He believed you wouldn’t. That’s why he wrote this.”

He nodded at the envelope again.

“May I come in? It will be easier to explain if you read the letter.”

Everything in me screamed Don’t trust this.

But Noah’s hand brushed my elbow—gentle, grounding.

“Door stays open,” he murmured, so only I could hear.

So we let Thomas in.

Thomas set the envelope on our coffee table like it might explode.

He sat on the sagging thrift-store chair like he’d sat on worse, though he carried himself with the practiced ease of someone used to other people’s tension.

Noah and I took the couch. My knee pressed against his wheel. His hand found mine and stayed there, warm and steady.

“I’m an attorney,” Thomas said. “I represented Mr. Peters. Before he was gone, he gave me very clear instructions about you.”

Noah stared at him. “About me?”

Thomas nodded once. “Yes.”

Noah picked up the envelope. His fingers trembled slightly—small movements that most people wouldn’t notice, but I did. I felt it in the way his thumb hesitated on the seal.

He opened it carefully and pulled out the letter inside.

The paper looked thick. Old-fashioned. Like someone had chosen it on purpose.

Noah unfolded it and began to read aloud, his voice quiet in the small room.

“Dear Noah,” he read. “You probably don’t remember me. That’s all right. I remember you.”

Noah swallowed and continued.

The letter explained that years ago, outside a small grocery store, Harold Peters had slipped on the curb and fallen. His bag had spilled. He hadn’t been seriously hurt, but he couldn’t get up right away.

Noah’s eyes tracked the lines. His voice slowed as he read the part that made my throat tighten.

The letter said people saw Harold. People glanced, adjusted their path, and walked around him.

Then one person stopped.

Noah.

In the letter, Harold described it plainly: Noah picked up the groceries, asked if Harold was okay, and waited until he was steady before leaving.

No rushing. No jokes. No awkwardness.

Just presence.

Just kindness.

Harold wrote that later, he realized why Noah looked familiar. Years earlier, he had done occasional maintenance work at a group home, and he remembered a quiet boy in a wheelchair who watched everything and complained almost never.

“You did not recognize me,” Noah read, voice catching slightly, “but I recognized you.”

The letter went on. Harold wrote that he never married, never had children, and had no close family who depended on him.

But he had a house. Savings. Accounts. A lifetime of belongings that mattered to him in the way ordinary things matter when they’ve carried you through lonely years.

He wanted to leave them to someone who understood what it felt like to be overlooked—and who still chose to see another person anyway.

Noah reached the final lines.

His voice shook when he read them aloud:

“I hope this does not feel like a burden. I hope it feels like what it is: a thank you, for seeing me.”

When Noah lowered the letter, silence rushed into the room.

I stared at the paper like it was some kind of miracle you weren’t supposed to touch.

Then I looked at Thomas.

“What does he mean?” I asked, carefully. “What did he leave?”

Thomas opened a folder and turned a page toward us.

He explained that Harold had arranged everything in a trust.

His house. His savings. His accounts.

Noah was listed as the sole beneficiary.

Thomas named the amount held in the accounts, and for a second my vision did something strange—like the room tilted, like my brain couldn’t find a way to fit those numbers into our reality.

It wasn’t endless luxury money.

But it was breathing money.

It was “we won’t panic about rent anymore” money.

It was “we can handle emergencies without falling apart” money.

“And the house,” Thomas said, voice calm, as if he announced life-altering news every morning with coffee. “Single-story. It already has a ramp. It’s about an hour from here. The key is in this envelope.”

He slid a smaller envelope across the table.

Noah stared at it like it might evaporate if he blinked.

“My whole life,” Noah said slowly, “people in suits showed up to move me… or to tell me I’d lost something.”

He lifted his gaze to Thomas, and there was something raw there—something younger than his years.

“You’re really here to tell me I gained something?”

Thomas’s mouth softened into a faint, genuine smile.

“Yes,” he said. “I am.”

He left his card, told us to find our own lawyer if we wanted, and then—quietly, respectfully—he let himself out.

When the door clicked shut, our apartment felt too still.

The laundromat hum below us seemed louder, like the building was trying to fill the space where words should have been.

For a long time, Noah and I didn’t speak.

Because our whole lives had been built around the idea that nothing good stayed.

That anything you loved could be taken away with a signature and a shrug.

This—this felt like a glitch in the universe.

Finally, Noah exhaled.

“I helped him pick up groceries,” he said, almost disbelieving. “That’s it.”

I turned toward him. My eyes burned.

“You saw him,” I said softly.

Noah looked down at the letter again, the paper trembling slightly between his hands.

“Everyone else walked around him,” he murmured. “He noticed.”

Then he looked up at our peeling walls, our crooked blinds, our secondhand life that we’d built piece by piece.

“He really did mean it,” he whispered.

A few weeks later, we went to see the house.

The drive felt unreal, like we were headed toward someone else’s life. The sky stretched pale and open above the road. Noah’s hand rested on my thigh at red lights, his thumb rubbing small circles like he was reminding himself—and me—that we were still here, still us.

When we pulled up, the house looked… ordinary.

Small. Solid. Quiet.

A ramp led to the front door like it had been waiting.

There was a scraggly tree in the yard, its branches thin but stubborn, moving slightly in the breeze.

Inside, it smelled like dust and old coffee.

The air had that closed-up quality of a place that had been lived in deeply and then left untouched for a while. The floor creaked under my steps. Light slanted through the windows, turning floating dust into tiny sparks.

There were photos on the walls. Not of grand events—just ordinary moments frozen in time. Books on shelves, their spines worn from being opened. Dishes in cabinets. A blanket folded on the arm of a chair like someone might come back and reach for it any second.

A real home.

The kind people grow up in and return to for holidays.

Noah rolled into the living room and turned in a slow circle, taking it in from every angle. His wheels made a soft whisper over the floor.

His face looked open in a way I didn’t see often—like something inside him had unclenched.

“I don’t know how to live in a place that can’t just…” He stopped, searching for the word. His throat bobbed. “…disappear on me.”

I crossed the room and rested my hand on his shoulder.

Beneath my palm, I felt the solidity of him—the man who’d survived alongside me, the boy who’d shared the window, the person who had always stayed.

“We’ll learn,” I said, my voice steadier than my chest felt. “We’ve learned harder things.”

Noah swallowed and nodded once, like he was accepting a truth he hadn’t allowed himself to want.

Growing up, nobody chose us.

No one looked at the scared girl or the boy in the wheelchair and said, That one. I want that one.

But a man we barely remembered had seen who Noah was in a simple, human moment—and decided that kindness mattered.

And somehow, against every rule we’d ever been forced to live by, something good had found us.

Finally.